JULIO VILLANI, TO BIND THE WOLD | Philippe Piguet

No one can live between two continents, two countries, without being deeply affected. Julio Villani’s personality is a construct determined by a life split between South America and Europe, between his native land of Brazil and France, his adopted country, between São Paulo, where he grew up, and Paris, where he forged his identity as an artist. This deliberate partitioning and the way Villani has conceptualized it gives both his life and work a dynamic dimension that, consciously accepted, paradoxically emerges as a self-determined unity.

While some would feel torn or divided, Villani gathers working matter, subjecting it to a reunification process. Where others would get lost in a schizophrenic maze, the artist clears a path that, in spite of its twists and turns, always follows an obsessional gaze that seeks to penetrate the secret heart of the world.

One cannot encompass two geographical realities unless seeking to change the world, to fold it up into the shape of a black square, sew it back and front; immobilise it through a machine célibataire or, on the contrary, through ceaseless rotation, activating the rhythmic cadence of the stride ; or still invent an entire new population of hybrid figures. These and many other unpredictable experiments have never ceased to inspire Villani and become part of his work in a spirit of utter freedom.

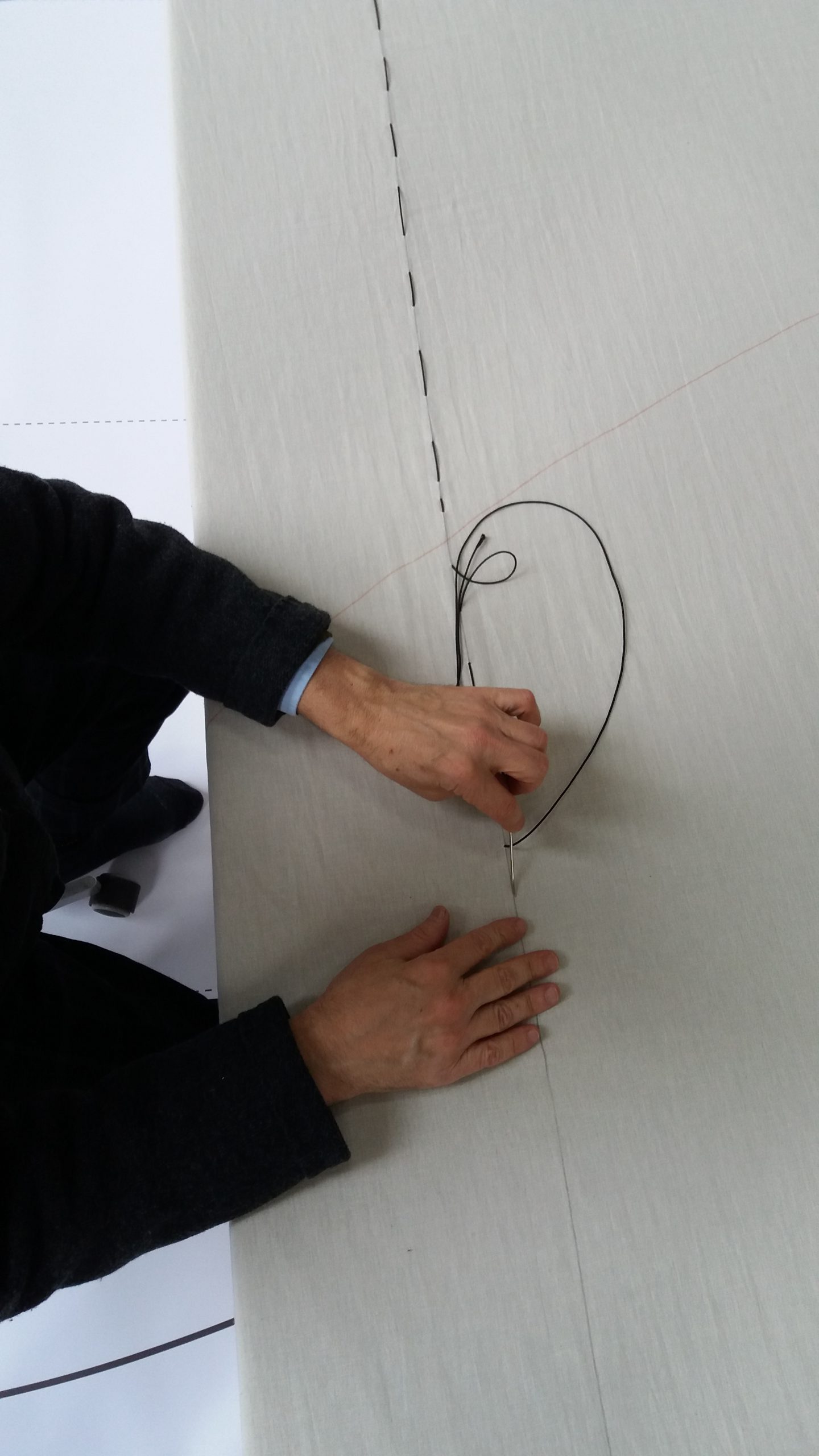

Cord, line, trace, loop, network, knot… Julio Villani’s art is inhabited by the idea of link, of connection. This is an integral part of his work and structures its every piece. Thus the concepts of pole, counterpoint, extremity, and even opposition, permeate each one of them. They are organized according to the idea of a back-and-forth movement, a coming and going, an exchange.

According to the artist, whatever happens occurs in this “in-between”, at the very heart of this interchange.

1 + 1 = 1 | Philippe Piguet

To grasp Julio Villani’s work, we must set aside all our preconceptions, question our usual perceptual modes. We must allow ourselves to be guided by the fleeting moods of a wandering thought, freed from dogma.

The artist has long been practicing a veritable artistic “anthropophagy”, feeding off a wide variety of source material. While he admits his fascination with Amerindian culture and customs and their infinite capacity for plastic invention, he also admits to the crucial influence of Arthur Bispo do Rosario. The latter began as a sailor and boxer, but, suffering from paranoid schizophrenia, he insisted that God had commanded him to create an inventory of the universe to be presented on the day he passed into the other world. After his confinement to an asylum, he spent endless hours in his cell sewing and tinkering with a wide range of objects, using whatever materials he could scrounge.

Julio Villani was also extremely receptive to the art of another fellow citizen, Alfredo Volpi, a master colorist who developed a stylized synthesis of Brazilian folk imagery. However, Villani admits that his encounter with Mondrian’s work completely altered his vision of the world. This initially resulted in a series of works that use subtle, sensitive geometries and reveal an intimate acquaintance with Lygia Clark’s unfolding paintings and Transformable hinged sculptures.

Moving between Dadaism and New Realism, Duchamp and Broodthaers, through Cubism, Surrealism, and artists such as Torres-García and Oiticica, Villani’s œuvre offers a variety of forms and contents that bears witness to the principle of a wide-ranging process of appropriation that lies at its foundation.

Traveling through Julio Villani’s work, we become aware that art can still provide answers to existential issues. The question of identity that weaves the backdrop to his approach can be understood not only through his use of the line to divide, connect, and balance, but also through his investigation of memory. Villani’s style of recuperation and the form of recycling he uses when transforming discarded objects enables him to intertwine two temporal frames to inform a third that gives the resulting work its singular identity. At first, there’s the object found by the artist, then something foreign is added, and their combination becomes the raison d’être of his art.

A batch of old notary deeds and worn photographs found in flea markets allows Villani to concoct an entire family – his “French family” as he calls it. Using the stories suggested by the photographs and documents, he does not hesitate to intervene in order to sneak in – in a sense, to carve out a niche for himself.

The difference between geology and genealogy is infinitesimal, as both present a palimpsest aspect leading to the formation of layers of space and time. Such a process feeds, embodies, and anchors Villani’s art, transcending frontiers and laying the ground for the emergence of a universal language.

TALES OF GULLIVER | Philippe Piguet

One must have seen his studio to capture the almost unlikely world of Julio Villani. Long established in Paris, the artist is the very image of his production: truly puzzling. At least he is never where you expect him to be, or where you thought you would find him. That is because Villani is an inventor who loves to take in a situation, an image or materials and immediately invest them, making them tumble into the order of a new language, of a distorted vision, never lacking humor, nor criticism, nor poetry. On the contrary: he likes to mix it all, in his own way, off the beaten paths of what’s considered “fashionable”.

The playfulness of his work proceeds neither from a foolhardy rush that would ignore reality, nor from a posture intended to hide it, in the name of some unknown concern. It is rather a way of highlighting this “little reality” to which André Breton dedicated a major text in 1927 – Introduction to the Discourse on the Paucity of Reality – and which Jorge Luis Borges further elaborated in 1941 in an opus entitled Fictions. The reasoning developed here, establishing a consubstantial relationship between fantasticality and the notion of literature – envisaged primarily as a fable and projecting us towards the outer borders of experience – finds in Julio Villani’s plastic approach a particularly clear echo. Like the writer, he quests after a form of anti-naturalism that guards against any narrative intention. His work refers rather to the invalidation of all cognitive referents, strives to bring discomfiture to the conventions expected from reality and to shake the foundations of intellectual rationality. In short, the art of Julio Villani is seized by a subversive thought that allows him to doubt reality. Therefore, his notion of representation does not escape metaphor because the reality to which it refers cannot be understood except through a metaphorical discourse.

The inventory of his work includes a sculpture made of three huge wooden cup-and-ball games, which the artist presents like toys abandoned on the ground by some passing giant. The game consists in throwing the ball in the air so that it fits onto the stem when falling down. Symbolic of a perfect wholeness between entities intended to join, the cup and ball is an object charged with meaning: it is at once the emblem of the relationship between life and death, man and woman, one and all, yin and yang, etc; the ensemble ball, stem and cord forming a singular trinity. These are no longer mere toys but the elements of a theater the monumentality of which invokes the tales in which stroll the heroes Pantagruel, Gulliver or Micromégas.

It did not take the artist long to react and retort to the site of the Abbey of Saint-Jean d’Orbestier. Seized by the powerful architecture, especially its clear stone arches which highlight the entire nave, Villani saw in them the shape of the fragile metal hoops through which one must drive wooden balls in the right sequence, using a mallet, during a croquet game. Julio Villani thus loves to subvert the facts with which he is obliged to compose; to divert them from their function, or reset them to respond to another register or again to transform their nature, so as to make them assume a new identity. Here, he has chosen to replace the sacred precinct by a playground, but one intended for a game of yore, its monumentalization catapulting it to the level of a fantasy – or a fable, to use two Borges’ terms.

By placing heritage, religion, leisure and dreamlike vision back-to-back, Julio Villani inscribes his proposal right in the heart of post modernity. Something surrealistic, if not surreal is at work in his approach, which recalls the recommendation made by André Breton to his troops when he encouraged them to give body to what they saw in dreams. With one crucial difference, though: Julio Villani is a daydreamer. The mind and the eyes always on the look-out for the world around him, he quickly sees “the little reality” it bears, and transforms it by a simple thought into something entirely new. This is magic, for – to use a consecrated expression used to define what artists are – he is among the “Magicians of the world” and invites us to imagine reality on the margins of canons and conventions. Of one thing Julio Villani can be sure: we do not come out unscathed from the experience he offers us.