MACHINES | Philippe Dagen

Machines have been part of the arts for more than a century, steam or coal engine, piston, gas, electric, electronic, cybernetic, computerized, digital – surely I forget some. There is hardly an avant-garde that has not been in one way or another marked by their irruption and their progress since the first locomotive crossed a landscape by Turner until… the examples are innumerable.

Of all these artistic machines, Villani’s favorites are the célibataires. Conceived by the engineer of lost time Marcel Duchamp, the machines célibataires produce nothing, as the adjective indicates, which does not mean they are useless. On the contrary: those are machines that are enemies of machines. It has often been observed that the appearance of a single machine célibataire dirupts the active machines so strongly that they break down or go crazy, becoming in their turn célibataires by a strange contagion.

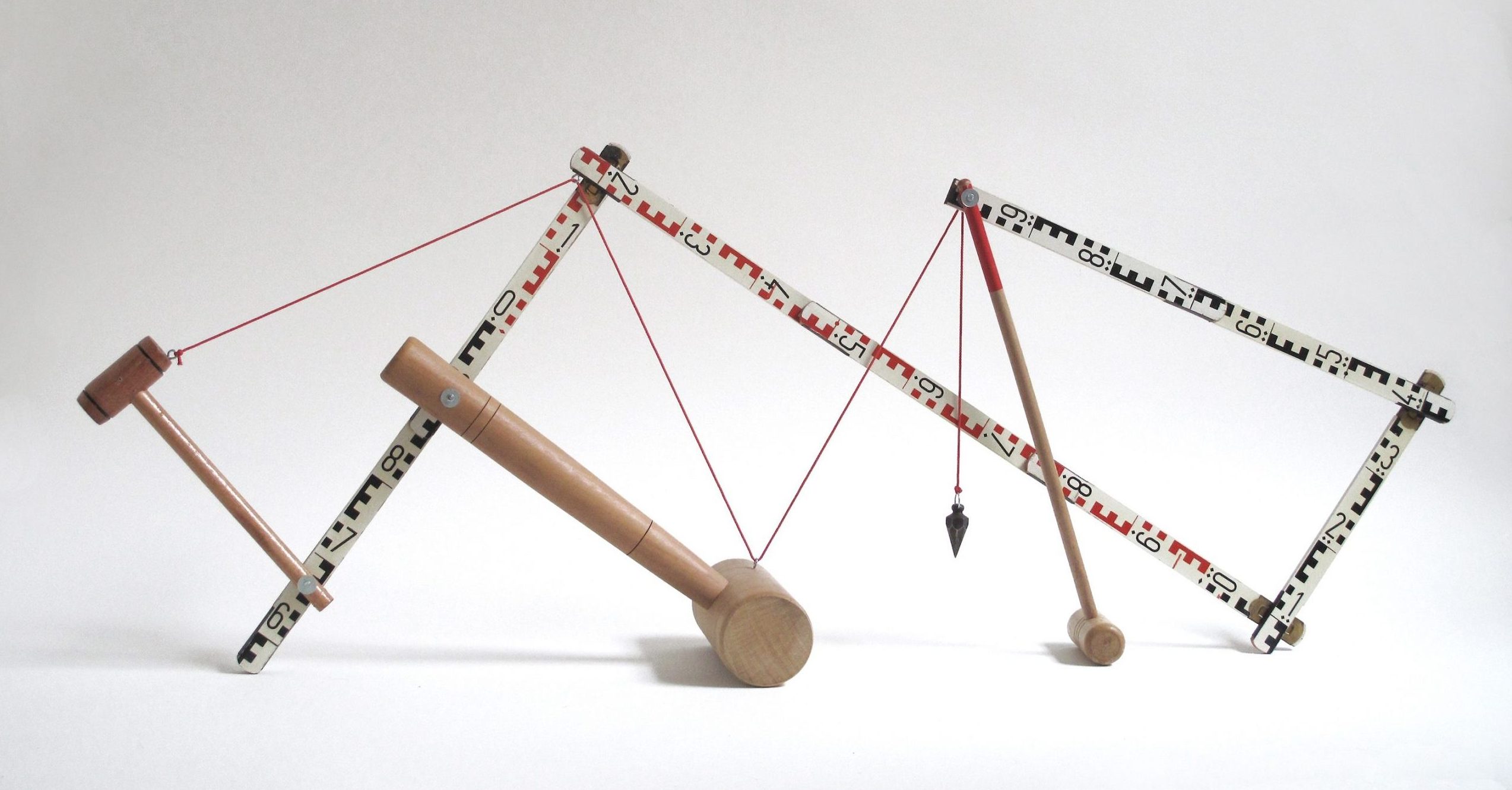

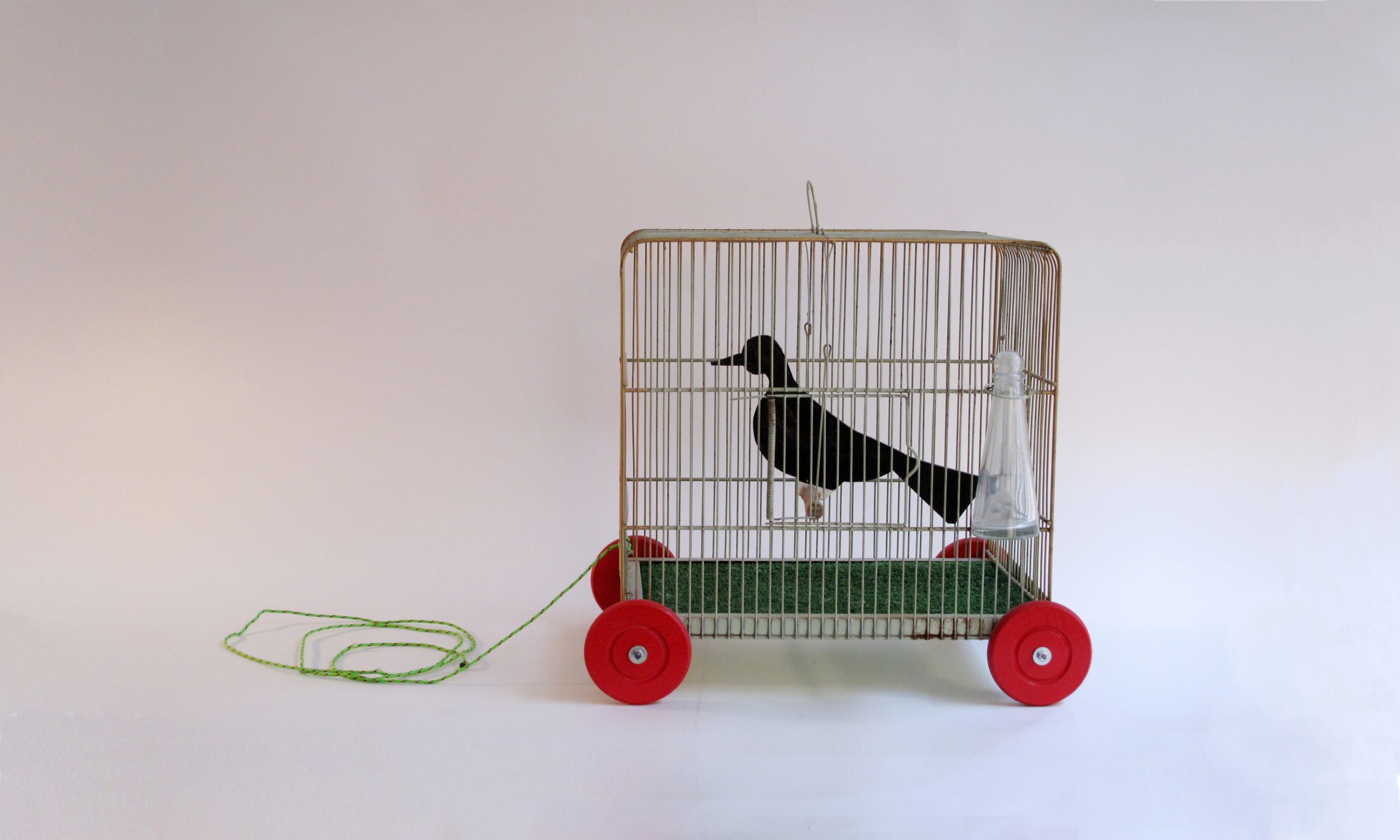

In this register, the engineer Villani proposes articles whose poetic absurdity cannot fail to leave one perplexed. One of them is a mobile machine to stay still. Composed of a conveyor belt – with its drive cylinders and motor – and a house in red and yellow painted wood, its singularity is that the conveyor belt spins uselessly under the house which remains immobile by the sole power of a string attached to the wall.

Among the hypotheses of interpretation which can be suggested, we will retain three. The simplest one is obviously that of an insult to the engine, whose regular efforts and impeccable technical design are rendered impotent by a string. One could easily see in it the revenge of the rudimentary on the complex. Other examples of the same confrontation would be the damage caused by a branch stuck between the spokes of a wheel, a bit of sand in a carburetor or a bit of water in an electrical circuit. These incidents should remind us all of the terrible frailty of indestructible machines.

A second consideration is hardly less obvious: the architecture, which Villani likes migratory, proves itself here, on the contrary, unmovable, thwarting the device that should walk it tirelessly on the black rubber mat. This could be a way of suggesting that the house is the same everywhere and that change is only an appearance. For an artist who lives on both sides of the Atlantic, the symbol would speak volumes.

The third would take the same direction: that movement is not perceptible even though its reality cannot be questioned, as the daily life of men demonstrates. They know that their planet rotates and yet they have the impression that their houses are immobile, held by invisible strings despite the rotation of the earth on its axis.

Another machine, obviously célibataire and duchampian, walks to better stay still – again the dialectic of mobility taken in reverse. It consists of a table and a stool. The table has a rear wheel, a pedal and a sawn bicycle frame. On the stool, Villani attached a wooden box that once held bottles of wine and inside it, a second, smaller wheel. At both ends of the hub, outside the box, two strings are attached, the other end of which is tied to two shoes, masculine, tan leather, rather chic. Pressing the pedals drives the chain and the big wheel, whose rotation is transmitted by a belt to the other wheel, a rotation that makes the shoes walk – or rather trample, since neither the length of the string, nor the general device allow them to gain even a few centimeters. They are condemned to walk without advancing, until he who pedals at the other end of the chain is exhausted. This construction is both clever and silly, in the claimed continuity of Duchamp’s bicycle wheel turning above the stool, a legendary readymade which Villani had the audacity to tackle.

The game of cancellation is at its height here: a real movement determines a movement that is no less real, but immobile – i.e. it hovers, an exercise well known to track cyclists who, unwittingly, practice this form of negative dialectic. In Villani’s case, it is certainly not without his knowledge. Just to add a little bit of wackiness, he superimposed on top of the wheel that makes the shoes sway a tin can of cookies, like a drum. But this drum serves absolutely no purpose. It is, according to the consecrated expression, of a splendid uselessness. All the more splendid as the idea of the shoes which do not advance can be associated with many legends and fables, stories of strollers or professor Sunflower, of statues and ghosts, of illusions and disillusions. You think you’re moving? You only give yourself the comforting impression of doing so.

The third machine is of a slightly different kind, although it is presented as two boxes – large display boxes, bill boards for the use of advertisers equipped with rotating systems. Here though, no publicity posters revolve, but a long paper roll on which Villani has drawn his life in the form of anatomical plates. The arteries and veins are the circulation routes, cities and ideas were made organs. It’s simple – of that obviousness that makes one wonder why no artist had thought of it before, so clever and effective is the diversion of this advertising material. (And who would complain that it is finally being used for something other than promoting a Hollywood movie, a beer or a line of teenage underwear?)

It is simple and it is disquieting. Because of the confusion between anatomy and geography, as Villani unearths here, quite naturally, the principle of the cosmic man and of the games of symbolic correspondences that were of such importance in the past and which we believe – modern and rational men that we are – to have renounced a long time ago; whereas this mode of thought, said to be archaic, has not disappeared, but continues to act in a more or less hidden way. Because of the scrolling too: the change never stops, but this change reveals to be the reappearance of the identical, an identical which would be the self, a self thus mapped, circumscribed and defined, in spite of the appearance of variation induced by the movement. We find here the strange – melancholic perhaps – dialectic of the immobility and the movement, central to Villani’s work and that consists one of its main interests.

Regarding art history, this double autobiographical screen in the form of billboards presents a final singularity: it brings together the readymade – the rotating billboards – and the drawing – the anatomical plates – and thus obtains a self-portrait, this ancient and probably immortal genre reappearing here under a rather unexpected guise.

Unless thought is so taken aback by this appearance that it comes to re-examine the history of the readymades and its proposes, in defiance of all critical and philosophical tradition, and to hold the readymade for a sort of self-portrait, the most rapid, the most brutal and the most obviously “signed”. If we stick to Duchamp, nothing less illegitimate: the decision to place a bicycle wheel on a stool or to hang a hat rack can only be justified as a pure decree of the artist’s will that modifies the order of the world according to his fantasy. A ready-made would be an autobiographical reliquary, like those made with objects (of art or not) by all that compose at home certain arrangements that – because they are disturbances – bear their mark.

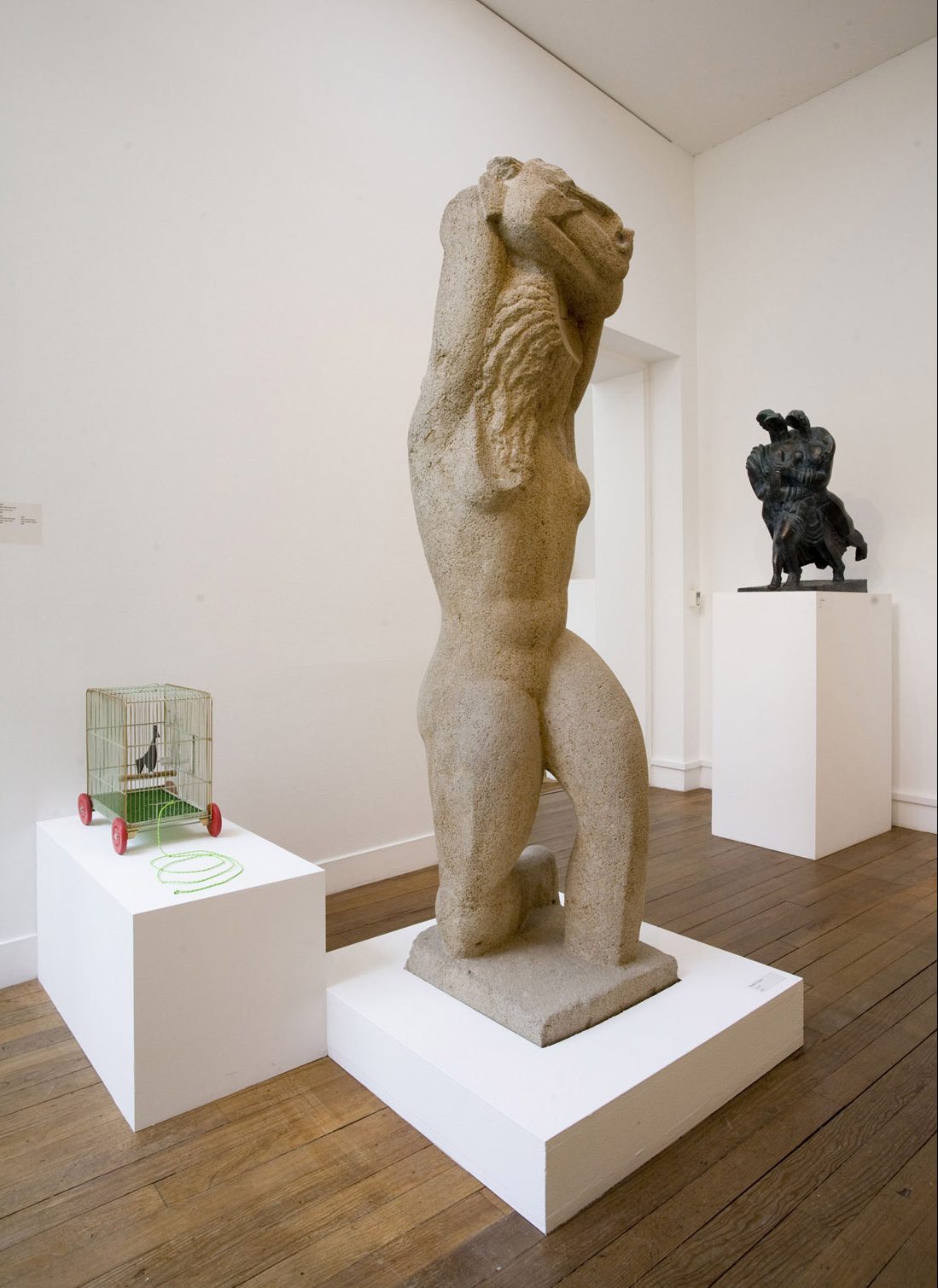

Villani’s machines are self-portraits in the form of readymade abetted and diverted.

.

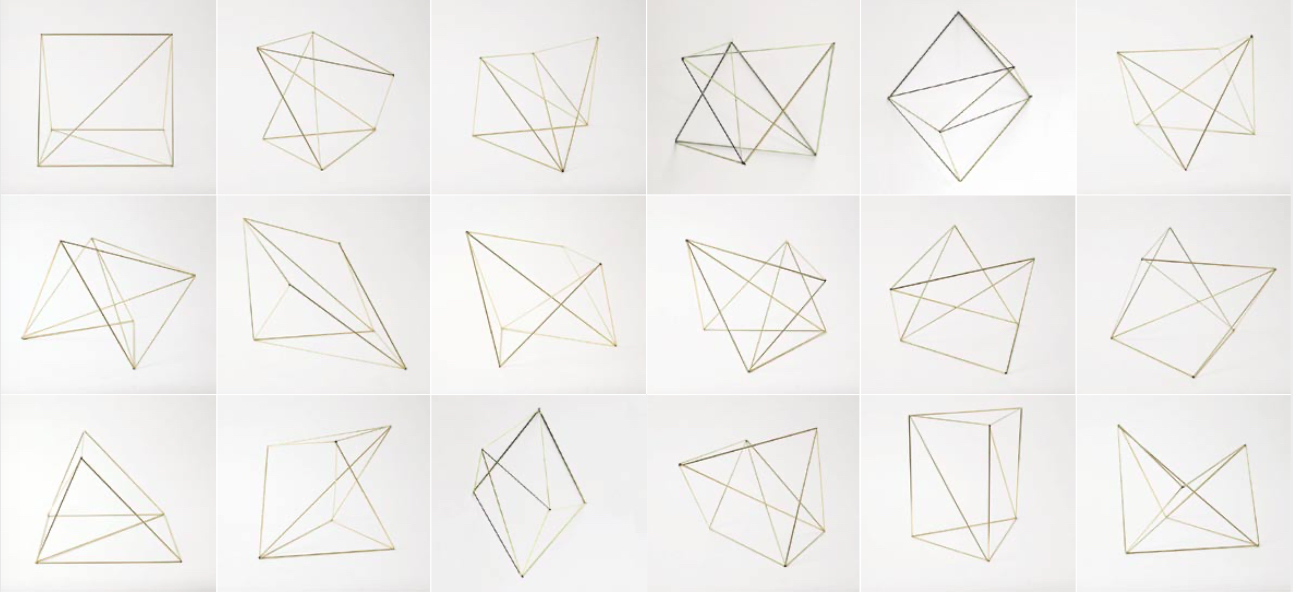

For more on machines and sculptures | ANARCHIVES