POETIC PRESUPPOSITIONS [1/2] | Fernando Cocchiarale

The cultural confluence of universes through which Julio Villani’s subjectivity sails (São Paulo – Brazil – Paris – France – Europe) has always been vital to the dynamics of his work. But though at its source, this confluence does not determine or explain his creative process, which is not confined to a simple expression of his personal life. The convergence of life and work in Villani’s case (as well as in that of most artists) is in fact only materialized through a poetic construction, understood in a similar sense to that conceptualized by Umberto Eco in Open Work : “as a project shaping or structuring the work”. This requires, therefore, that the boundaries that separate just as much as they communicate the historicity of a given artistic context be transcended, and come–together with the poetic reverberation of the personal sphere.

In Julio Villani’s work, the correlation between context and poetics is always consummated visually; even his embroidered texts series – P(l)ane, line and point, alluding to one of the most famous texts by Wassily Kandinsky, Point, Line, Plane – are produced (and normally perceived) as drawings, since they were designed to awaken the graphic power of the written word. A similar correlation can be detected in the work of Artur Bispo do Rosário – an influence pinpointed by Villani himself – whose embroideries are apprehended first as a visual experience, and only secondly, read: discovered as a verbal inscription by the observer.

Villani’s work is thus opposed visually to the semantic-verbal narrative that drives the production of many contemporary artists – especially those engaged in an overtly political art, who frequently believe in the equivalence of visuality and discourse. Approached through the long worn out notion of “language”, these modes of communication could easily “translate” into each other without great loss to either one or the other.

From design to production, Julio Villani’s works swim against the tide of this equivalence. The artist’s position does not conceal some retrograde appetite for “formalism” – a concept that modernist deconstruction, promoted by postmodernism and more recently by postcolonial thought, has elected as one of the most pejorative adjectives in the contemporary art vocabulary, and therefore adopted as such by the latest generations of artists, curators and other contemporary intellectuals. There is no intention in any way to challenge here the use of this word in the field of the visual arts, nor to assert a complete impermeability between visual and written meanings. There are, of course, permeable zones between these two types of discourse. But the most favorable of them (the ambiguity of which is produced as a positive cultural value) can emerge only through invention and poetic construction.

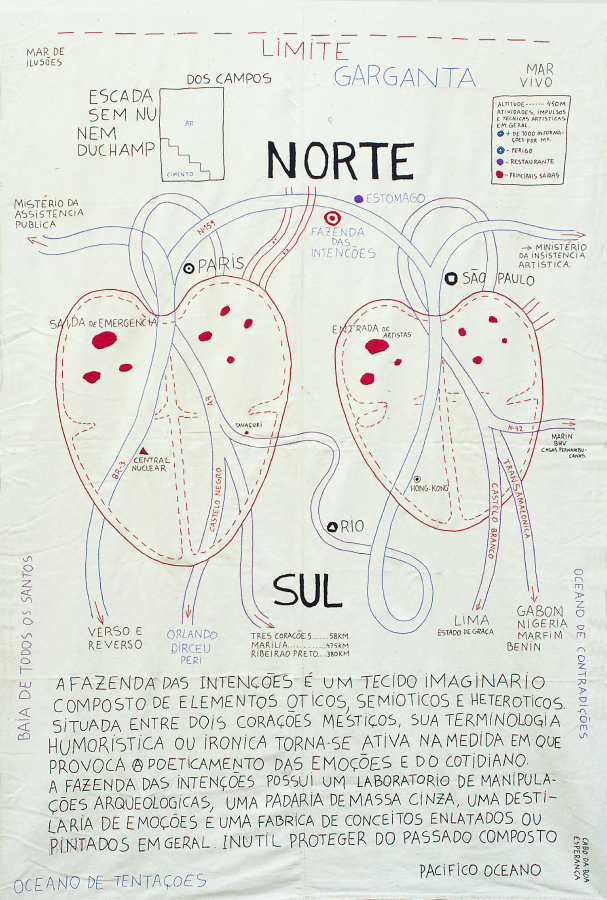

Julio Villani knows how to navigate and explore this area, a skill that is revealed as much by the titles of his series and specific works, as by the semantic charge of the images themselves, by the chromatic and formal elements he cites, by the appropriation of the objects he claims.

POETIC PRESUPPOSITIONS [2/2] | Fernando Cocchiarale

The individual poetic contribution of an artist has become indispensable to the modus operandi of European art since the Renaissance, and its assimilation as a bounty – be it by specific communities or by largely (quantitatively and / or qualitatively) inclusive social groups – has become more evident since the 1950s and 1960s. With regard to this assimilation, modernity has set itself apart through its search for pure plasticity, as opposed to the naturalistic representation which triggered, in different ways and to different degrees, European art production since the Renaissance.

Thereafter, the search for a pure form of art – devoid of allusions to semantic references to any elements not directly structuring the work, and understood as a visual language consisting purely of shapes and colors – would be rooted in the modernist consciousness as the sole approach to the pictorial plane. It is important to note that modernity has not always cruised in the crystal clear waters of purity. The initial interest of modern art for traditional cultures, for the Unconscious (Surrealism), constitute an eclectic field of repertories and references, which share as a common trait the search for the core, for the very essence of all artistic production; this lays the all important foundations for the renewal required by bourgeois society and its technological apparatus, be these real (iron works and engineering, Ford’s assembly line) or imaginary (Frankenstein, Russian Constructivism and cinema, for example).

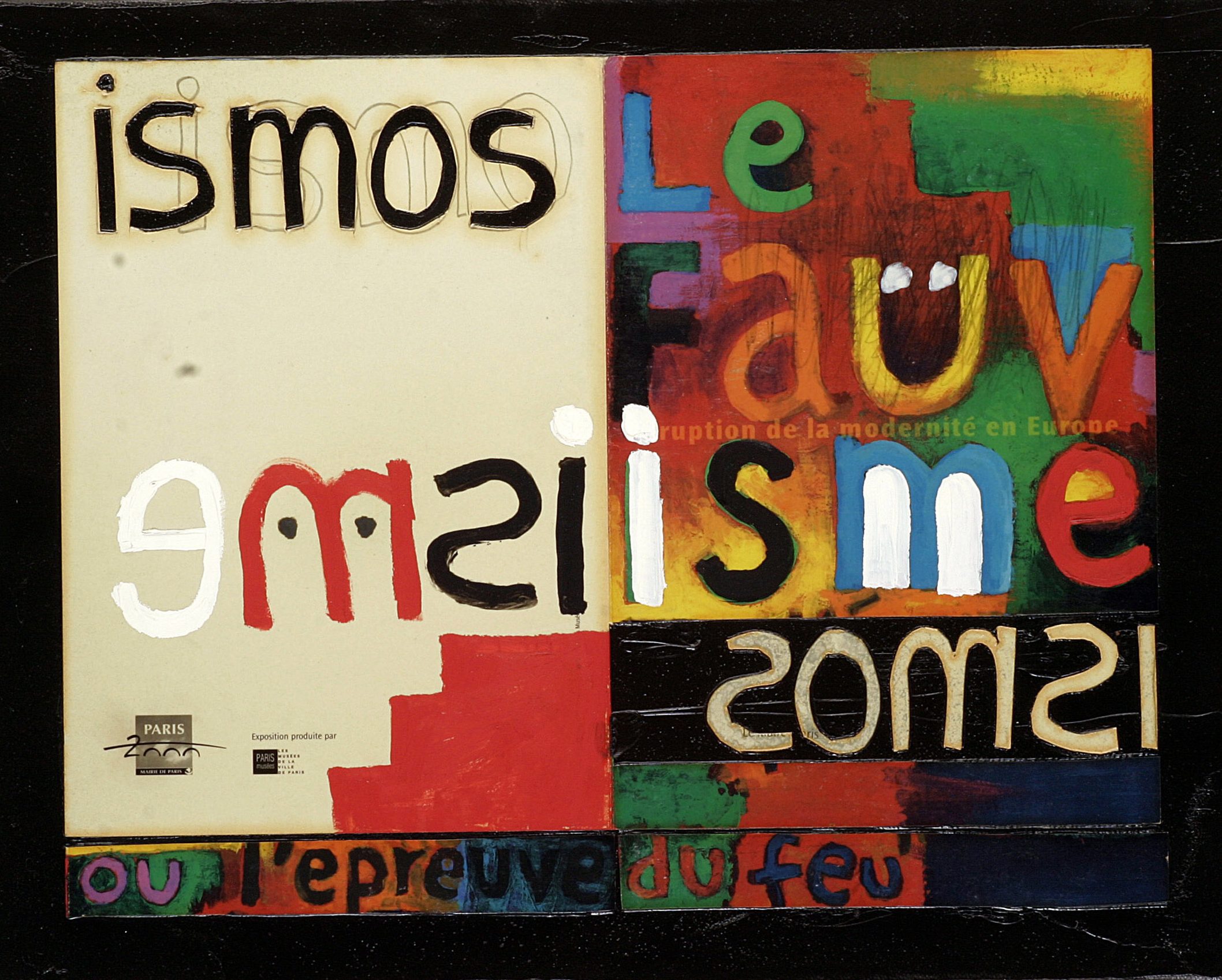

The poetic outcome of this debate is constantly revisited in Villani’s work. There is a correlation between his choices and the various references to Modernity that he chooses to incorporate. But this correlation cannot be seen or evaluated only through the lenses of order and purity in which they were originally created. Sixty years have passed since the emergence of contemporary art – with its first examples emerging as early as the first half of 1950s in the Japanese Gutai group, the Combine paintings of Robert Rauschemberg, Anglo-American Pop, French New Realism, or in Fluxus’ radicalism. It is to be expected that in lieu of all the modernist ‘isms’, we shall see the flourishing of cross-cultural references (therefore impure or hybrid ones, in perfect conformity with the production method of re-editing all means and elements at hand), which have invigorated, and still today animate, contemporary art and culture.

The reluctance of the last two or three generations of critics, artists and curators to fully embrace modernism denotes a desire to oppose its early historical form, and the broad opportunities it offered to the production of art in our times. In a sharp critique, Hal Foster writes: “The conservative postmodernism (…) is defined mainly in terms of style, it depends on modernism that, reduced to its own worst formalist image, is countered with a return to narrative, ornament, figuration. This position is often one of reaction, but in more ways than stylistic – for also proclaimed is the return of history (the humanistic tradition) and the return of the subject (the artist / architect as the master auteur). (…) In art and architecture neoconservative postmodernism is marked by eclectic historicism, in which old and new modes and styles (used goods as it were) are retooled and recycled [1] ».

Through Foster, one notes that the poetic core of Villani’s work fights against the slipstream of a substantial part of the contemporary artists, who avoids and even rejects modernist values, in the name of strict citation and re-editing of visual repertoires adopted by the so-called traditional cultures or pre-modern European art.

Trans-cultural synthesis may be the link between personal experience and the poetics of Julio Villani’s constructive process. Besides avidly absorbing modernist references (not purely in terms of their forms, but in their essence also), the artist acknowledges them to the full, to better rebuild and update them, (literally) superimposing chromatic shapes and graphics on gleaned images, or simply creating – with what ease! – with everyday objects. This hybridization of formal and iconic repertoires (also perceptible in his interest in the visual systems of other cultures), far from estranging him from methods and processes compatible with the present day socio-historical context, inscribes Villani’s work in a rare and original register amidst contemporary poetics.